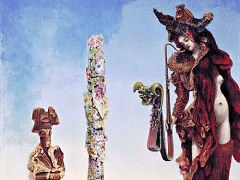

City with Animal, 1919 - by Max Ernst

Max Ernst came to artistic maturity during one of the most fractious periods in European history. Both politically and culturally, the second decade of the 20th century was a tumultuous period which brought major change to Europe: World War I broke out, the Russian empire collapsed, and avant-garde organizations proliferated in the arts. In Germany, where Ernst was born to an amateur painter and his wife in 1891, the journal Der Sturm began publication in 1910 and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) group was formed in Munich in 1911. These and many other manifestations of the avant-garde provided the impetus for Ernst's rejection of the academic tradition represented by his father's paintings.

Ernst was conscripted into the military as an artillery engineer during World War I and was twice wounded, yet managed to pursue his artistic interests throughout the course of the war, exhibiting in Berlin at the Der Sturm gallery in 1916. The following year, he published "Vom Werden der Farbe" ("On the Origins of Colour"), an article that paid tribute to Marc Chagall, Robert Delaunay, and Wasily Kandinsky, reflecting Ernst's aesthetic interests at the time. Landscape similarly represents a synthesis of artistic idioms gleaned from his peers: the pictorial logic invokes a Cubist idiom, while the palette and animal forms recall the paintings of Heinrich Campendonk and Franz Marc.

While Landscape predates Ernst's involvement with Cologne Dada in the late 1910s and the Surrealist movement in the 1920s, the startling juxtapositions and fantastic imagery foreshadow this later work. Active among the Surrealists, who plumbed the recesses of the mind and the world of dreams for their imagery, Ernst would develop his own highly personal iconography, including the man with the bowler hat and the bird seen in this painting. The former has been interpreted as a reference to his father, while the latter evolved into the artist's alter ego "Loplop" and appeared frequently throughout Ernst's oeuvre. The prominent eyes - presaging the Surrealist fascination with vision - compound the ambiguity of the canvas: they appear frontally in the profiles of the animals in the foreground and are partially obscured in the landscape below the figure with the bowler hat. Resistant to ready interpretation, this painting is perhaps best understood in terms of Louis Aragon's comment that "Max Ernst's thought must be grasped at that point where, with a bit of color, some sketching, he tries to acclimate the specter he has just hurled into an alien landscape, or at that point where he places in the new arrival's hand an object the other cannot touch."