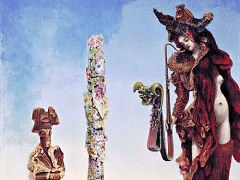

Woman, Old Man and Flower, 1923 - by Max Ernst

Dada had, necessarily, a brief life. It was vivid but ephemeral; a rebellious upsurge of vital energy and rage.It resulted from the absurdity, the whole enormous "schweinerei" of WWI. The young came back from that war in a state of stupefaction, and this rage had to find an outlet. Some of the most flamboyant members of the international Dada movement were never to be heard of again as consequential artists. They had their moment of significant exasperation, and nothing came along to replace it. But not Ernst.

From the moment he left school, he had begun assembling the materials for a long lifetime in art. More precisely he had looked into the history of his own first years with the lucidity that came from a precocious familiarity with psychoanalysis. And although he detested the Prussians' military ambitions and resented their authority over the Rhineland, he did acquire, however unconsciously or unwillingly, a Prussian determination to stick to what he wanted to do and never leave off until it was finished.

In Woman, Old man and Flower, 'As Ernst's series developed, this original surrealist identity with its heroic overtones became submerged, and it has remained submerged vis-a-vis art history, which has viewed the paintings only in light of their basic fascist identity, not in terms of this repressed surrealist one, which is repressed in the best and most obvious Freudian sense and therefore requires release, possibly in the surrealist friendly arena of wit or dreams.'