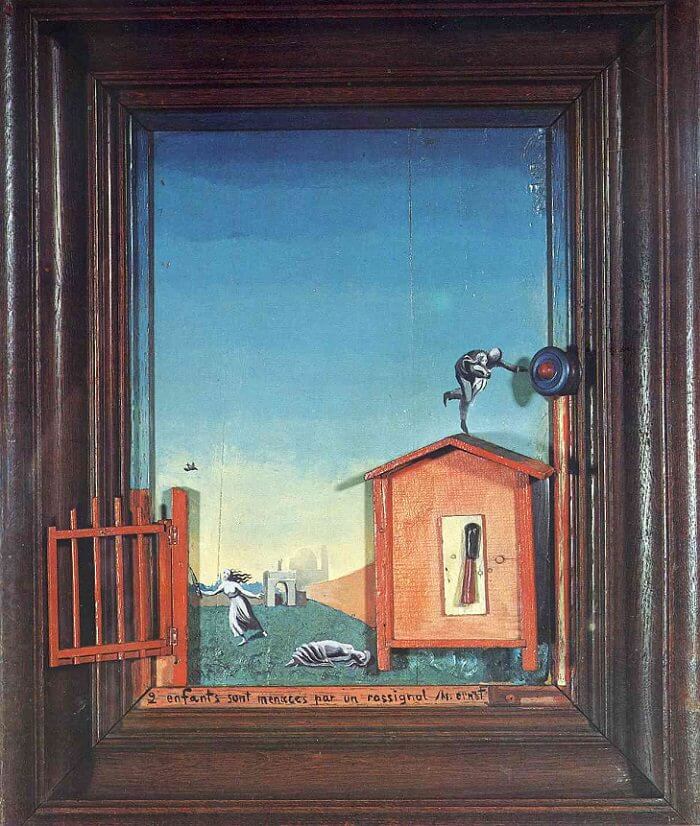

Two Children are Threatened by a Nightingale, 1924 - by Max Ernst

A red wooden gate affixed to the painted surface opens onto a painted scene dominated by blue sky. At left, a female figure brandishes a small knife; another falls limp in a swoon; a man atop the roof carries off a third, his hand outstretched to grab a real knob fastened to the frame. The title of the work (inscribed at the base), was inspired by a fever dream the young Max Ernst experienced while in bed with measles.

As Ernst recalled in third-person, the dream was "provoked by an imitation-mahogany panel opposite his bed, the grooves of the wood taking successively the aspect of an eye, a nose, a bird's head, a menacing nightingale, a spinning top, and so on." A poem Ernst penned shortly before making this work begins, "At nightfall, at the outskirts of the village, two children are threatened by a nightingale."

In discussing his life, Ernst recalled seven significant events that altered his frame of mind and approach to art marking. Four of these occur in his youth when in 1897 when he first began to experience "the feeling of nothingness" after the death of his sister, Maria. It is also at this time he contracted measles and had hallucinations of various figures, most notably "a menacing nightingale". Ernst recalls being both scared and excited by these hallucinations. Once his measles were cured he took up the hobby of "looking" in which he would stare at "wood-panels, clouds, wallpapers, unplastered walls," etc, in an attempt to let his imagination take over and create new visions. He used this method while drawing and painting as a way to pry fantastical imagery out of his subconscious.

Ernst was also inspired by his father Philip, who had been commissioned by the church in their hometown of Bruhl (Germany) to recreate classic masterpieces. Philip would often take liberties with the originals and substituted the faces of his family and friends for those of the saints and angels. Despite openly rejecting his father's use of realism, many historians believe that Philip's role in Max's life influenced his painting style greatly. In 1898 Ernst watched his father paint a realist landscape and began to feel the need to connect the creations of his imagination with the imagery of the natural world.

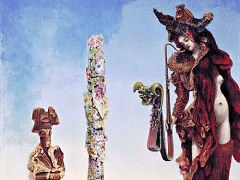

The need to merge the natural and mythical worlds was reinforced in 1906 with the death of his beloved pet cockatoo and the birth of his sister, Loni. Both events caused Ernst such anxiety that he allowed his imagination to connect birth with death, as well as the existence of animals with humans. He went about creating a bird alter-ego named Loplop ("a superior of birds") who is believed to be the voice and inspiration for much of his work. As such, Loplop was a manifestation of his confusion and psychological anguish.

Rather then repressing his childhood memories, and the German cultural symbolism he was raised with, Ernst followed Sigmund Freud's dictum to"...analyze the symbolism in his dreams and other unguarded thoughts." Many researchers quote Freud's Totem and Taboo to explain Loplop's existence, suggesting that this alter ego "functions as a symptom of Ernst's desire to create an art of the unconscious," as well as a symbol of honor, protection, commemoration and inspiration that may not be accessible outside of Ernst's mind. Simply put, he worshipped Loplop just as many indigenous religions worship totems. Versions of Loplop are found most notably in Loplop, Superior of the Birds, Ocell de Foc, and Ubu Imperator. Samantha Kavky notes that Loplop is an ever-changing character, "ranging from a whimsical humanoid to menacing bird," reflecting Ernst's conflicts with his sexual identity and personality. Marcel Duchamp expressed a similar outlet with his alter-ego, Rrose Selavy. However, unlike Ernst, Rrose Selavy was treated as an entirely different human being while Loplop was treated as more of an artistic symbol and outlet of inspiration.